---------------

"We were shot at in cold blood - there was no warning," recounts Ike Makiti, a survivor of the Sharpeville massacre, as he stands by the graves of the township cemetery.

It's being hurriedly spruced up in time for Sunday's 50th anniversary and the arrival of VIPs.

Mr Makiti, was just 17 at the time of the shooting, a schoolboy and an active member of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC).

He was heading back to school just after lunch on Monday, 21 March 1960, when he heard the sound of gunfire.

"We thought it was just firecrackers at first, then it became clear when we saw the blood that they were shooting at the people. Most of them were shot in the back, as they were trying to run away. It was clear that this was something serious."

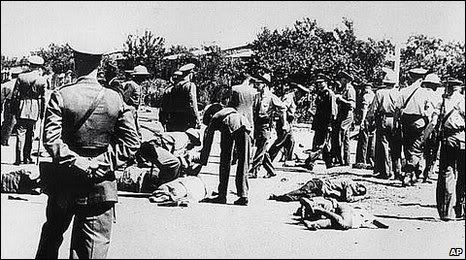

Fifteen minutes of shooting transformed the massacre into one of the most iconic moments of the liberation struggle.

It marked the start of armed resistance and the banning of both the PAC and the African National Congress (ANC).

Unemployed survivors

Thousands of protesters had gathered in Sharpeville, just south of Johannesburg, to protest at the use of the infamous passbooks, or "dompas", that every black South African was expected to carry and produce on demand.

It governed a person's movement, was a tool of harassment and was one of the most hated symbols of the apartheid state.

Sixty-nine men, women and children were gunned down on that day, killed when police officers opened fire on the crowd.

The police station - where they had gathered - is now a memorial to the dead.

As South Africa prepares to remember Sharpeville's 50th anniversary with Human Rights Day, there is unease in this run-down township.

People like Ike Makiti who subsequently served five years in jail on Robben Island for being a member of a banned organisation, are disappointed that the promises of the new democratic government are not being fulfilled.

"Most of the people who survived that massacre are not working," he says. "I'm not saying they should be fed sitting down, but they should be provided with work."

Sharpeville's small shopping precinct is in a dilapidated state and many of the buildings have been boarded up. What remains is a small fashion shop, a hair salon, a butcher and a modest bar.

Soured mood

But two schools have closed recently and there are no sports facilities for the youth.

Tsoana Nhlapo, who represents an organisation called Sharpeville First, speaks for the younger generation - descendants of those who witnessed the Sharpeville Massacre.

She is pushing for the township to be recognised as a national heritage site, for an apology from the state for what happened here and, as in many other poor areas in South Africa, for delivery of better infrastructure and services.

"When apartheid was still rife we were complaining that the four-room houses were like kennels, they're not of good quality, but what happens now they're in power is that they're building even smaller ones.

"Are we missing the point somewhere? Do we remember what we fought for?"

South Africa's ruling party, the ANC, is accused of not delivering the basics like housing and jobs to the very people who fought for liberation.

The row has soured the planned celebrations for the 50th anniversary in Sharpeville, with some events even cancelled for fear that they could spark riots.

It mirrors the mood in a society dubbed the most unequal in the world and serves as a reflection of a new type of struggle South African politicians are having to face.

0 comments:

Post a Comment